Block Bots. Reduce Risk. Keep Pace With Threats.

Netacea™ delivers AI-Driven threat detection and response to combat the most sophisticated bot attacks effortlessly. Unlike traditional bot solutions, Netacea is agentless, invisible to attackers. Delivering a truly autonomous response to automated threats, InfoSec and Fraud Prevention teams can protect revenues and customers with confidence.

Protecting billions of transactions per day at some of the largest brands across retail, fashion, streaming, travel and gaming.

84%

Reduction in API abuse

American big box retailer stops billions of malicious API requests daily

View case study$21,567,780

Annual savings in fraud per year

Leading global retailer eliminates account fraud attempts for good

View case study£1,000,000 +

Saved by halting streaming account theft

Global telecommunications provider saves millions by stopping automated threats

View case study

Traditional bot protection is broken. Defences can't keep pace. Attackers win.

Detecting and stopping bad bots is crucial for effective online fraud prevention, but staying ahead of their fraudulent automated activities and rapid adaptation can feel impossible.

Netacea's AI-driven bot protection technology provides control, saves time, and automates critical manual tasks. Delivering the most effective and accurate bot detection and mitigation mitigation to combat a new era of threats.

Forrester Wave 2022

Netacea Ranked #1 For Bot Detection by Forrester

Forrester, a leading research organization, has identified Netacea as a Strong Performer in its 2022 evaluation of the bot management market.

The Netacea Difference

What Makes Netacea Different

Hands-free detection proven to block bots 33x more effectively, with 0.001% false positives.

Stop bots prior to execution with powerful defensive AI continually enriched by large datasets. 33X better performance than competitors.

Large Threat Modelling

Trained on 100s of billions of weekly requests to detect markers of adversarial intent

Truly Autonomous Response

Trusted by SOC teams with a false positive rate of just 0.001%

Centralised Capability

One pane of glass, consolidating multiple legacy solutions

Achieve Total Visibility Traffic Across Websites, Mobile Apps and APIs With a Single Simple Agentless Integration

Low latency high throughput

Powerful edge computed threat analysis which doesn't impact customer experience

Eliminate Detection Gaps

Reduce threat dwell times, by spotting attacks that simply can't be detected using agent or client side challenges or detection methods.

Self managing architecture

A lightweight integration requires no manual updates to stay ahead of threats.

Invisible server side deployment

No code for attackers to reverse engineer, fails open

No Visible Code or Javascript for Attackers to exploit, reverse engineer or exploit.

Netacea makes attacking your websites, apps or APIs costly for attackers.

Visible defenses,make it easier for attackers to reverse engineer and bypass controls.

Netacea is invisible to bot operators, evolving to stop attackers as they retool again and again. Removing the motivation to attack by making you a costly tough to crack target.

Protect high-profile events and products using real time data and dark web intelligence. Build long-term strategies with attack surface intelligence.

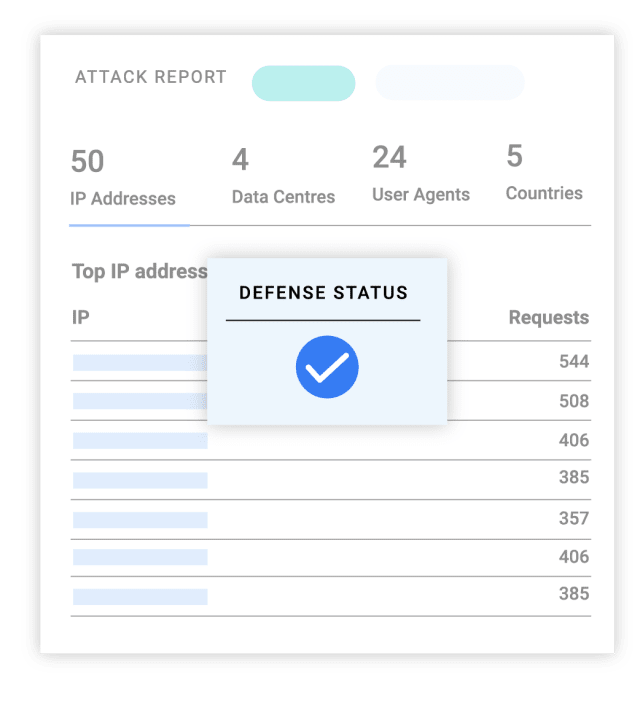

Granular Real-time Analytics

Visualise attack paths, perform forensics and uncover anomalies in a single dashboard

Low latency SOC Integration

Feed intelligence directly into SIEM, SOAR and XDR platforms with sub 1 second latency

Targeted research

Collect insights from thousands of bot communities with bespoke tools

Why Netacea

Netacea Redefines Bot Protection for Enterprise.

Legacy Controls

- Complex to deploy, expensive to maintain

- Limited client-side detection

- Slow, tedious and manual agent updates

- Bots attack undetected for up to 18 weeks

- Visible, easy to bypass or exploit

- False positives traded for decreased detection

Netacea

- Agentless, Full Attack Surface Visibility.

- Analyze Intent, Detects 33x More Attacks.

- Automated Server Side Updates.

- Real-Time Active Attack Detection & Response

- Invisible to Attackers, Tough to Bypass

- Ultra-Low False Positive Rate of 0.001%

- Fast, No Code, Single Deployment

Protect Websites, Apps and APIs against:

Automated your detection and response to a range of brute force attacks that seek to target critical web systems and information.

Explore Our Web, Application and API Security Solutions

Advanced Bot Protection

Netacea's advanced bot protection software. Protecting enterprise for a new era of automated threats.

Bot Attack Intelligence

Augment your existing security setup with bot attack intelligence, a threat feed specifically for bots that integrates with your SIEM,SOAR and XDR platforms.

Threat Intelligence Service

Understand the minds and activities of cybercrime networks targeting your business. Infiltrate the most guarded threat groups and gain threat intelligence insights on those posing a risk to your business.

What our customers think:

Flexible, Fast, Low Cost Integration

Never deploy agents again, discover how our server side approach allows for a swift and cost effective integration. A single deployment to cover Web, App and API using the tech you already have.

Resources

More From Netacea

The Bot Management Buyer's Guide

Know the key questions and criteria to ask before making your bot management vendor selection.

Netacea Receives Top Score for Detection of Bots in Forrester Wave™

'"Netacea consistently punches above its weight in thought leadership and research." – The Forrester Wave™: Bot Management, Q2 2022 report. Find out why Netacea leads the pack.'

Death By a Billion Bots

Uncover the accumulating business cost of malicious automation in this report from Netacea, gleaned from a major industry survey on the true impact of bot attacks.

Book a Demo

Book a Netacea Demo.

Book a time and date that suits you. Learn how Netacea helps enterprise brands detect and stop bot attacks across websites, apps and APIs.

- Unrivalled threat detection. Spot up to 33x more threats.

- Incredible Accuracy. 0.001% False Positive Rate

- Unified Protection For Websites, Apps and API.

- Specialist Bot Threat Intelligence